During a recent flight, we found ourselves in a situation that reminded me of Michael Masterov. It was uncomfortable, but good uncomfortable.

We were en route for a quick hop from Brantford to Hamilton, Stuart co-piloting, for a quick visit to the Warplane Heritage Museum. (What a great URL!). It’s only a five-minute flight, so we listened on Hamilton’s ATC frequencies most of the way. It was less busy than I expected, considering that they had a closed runway due to construction, and a scheduled landing-fee-free fly-in, but there was enough to keep paying attention. Incoming traffic was initially routed for the relatively small runway 24, which would have required us to fly past the airport on the north side, then do a three-point-turn.

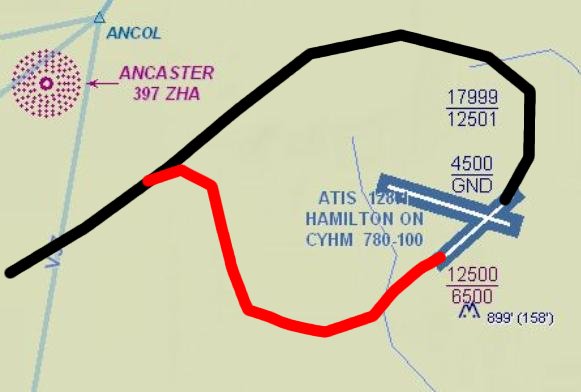

Plan change #1: at one point, ATC decided to expedite us by rerouting us to the opposite end of the same runway. The calm winds were fine with that plan. We were getting a little too close to make the change comfortably, but went with it. In the case of busy airports, this can lead to trouble, so big jet drivers would normally turn down such an offer. Here was the new plan:

We were now somewhat fast & high for the shortcut, so down came the throttle, the wheels, the flaps. We sank and slowed, did final checklists, and maneuvered to line up. Just then, a WestJet 737, having finished his pre-takeoff checks on the ground, reported ready for departure on the same runway. Plan change #2: ATC told us to go through the final approach course, so as to give the jet a little more time. OK, the airplane is running a little low on energy, but can do. The trees and buildings are getting large, but the weather is great.

What the …? After that little jig, now on our final approach, the jet was still sitting on the runway in front of us. Plan change #3: seeing that there wasn’t enough time to have the 737 take-off before we got there, I asked ATC whether they’d like us to do a 360 delay turn. (If they had not replied in the affirmative right away, I’d have gone around, climbing, giving up on this plan-change-close-to-the-ground business.) The controller said “left or right, your choice”. I went right. At about 300ft above ground. With gears and landing flaps and low power.

A small increase in power arrested the descent rate, but with all that drag hanging off in a turn, we didn’t climb either. I soon recognized my discomfort at maneuvering that close to the ground, and the proximity of the radio towers right in the middle of my arc, and considered my options. Giving up (flying away at full power, to try again in some minutes) was possible. Maintaining the status quo was possible, but only with split focus on instruments (to make sure we don’t go too slow / low) and the outside (to stay away from the towers). I chose something in between, adding a little extra power to start a gentle climb, but otherwise completed the turn.

About 90 seconds later, we were back at the circle starting point, only higher. The runway was now clear, so we were cleared to land. Again decision time: being too high makes it a problem to land on a short nearby runway, so go around or still try to land? We did land, albeit long, and ended up with moderate braking to stop comfortably on the remaining runway. The taxiing was uneventful, the museum visit delightful, and the later return trip was fine, with Eric navigating by ground references & flying.

The Michael Masterov connection is this particular usenet posting from 2005:

… most recreational GA

pilots don’t take enough risks. They are overly conservative, and as a

result don’t fly enough in a sufficient variety of conditions, don’t

acquire enough new experiences, and never really develop the skills,

knowledge, and confidence to handle the unexpected. Then, when the

unexpected happens they bend airplanes – or worse. …

It’s a matter of short term vs long term safety. …

We had the option at at least four decision points to get out of the increasingly uncomfortable landing. But I believe Michael: that within reason, it is a good thing to practice the uncomfortable, to experience riskier corners of the envelope, to make decisions in situ instead of by rote, to make the dangerous safer.