I’ll pat myself on the back for hosting a weblog of such grand stature that even individuals from the islamic Kingdom of Saudi Arabia come across it. At least one such individual did, looking for images of “she hottie” (sic) on google.com.sa, finding this old article and this one. Glad to be of service in some minor furtherance of the liberalization of that country.

Often when bad news is announced in some public forum, a bunch of people will reply with “… I will include X in my prayers …”. People may or may not pray for me should something naughty happen, but I wonder whether they think it would “work”.

Of course, prayer is a religious action, and as such, is platonically segregated from the world of logic. Still, how does a believer think? Does she believe there is a causative or even correlative relationship between prayer and the desired outcome?

The very same god dude who capriciously allows or makes bad things happen will suddenly pause, take heed of this most recent batch of prayers, and change his “oh so incredibly big” mind? How inflated the believer’s sense of self-imporance!

How many times would a prayer have to go unanswered (i.e., not alter the outcome from established probabilities) before a supplicant should suspect that perhaps they have no effect at all? Would even a lifetime of disappointment fail to shake the faith? Would any dare subject such an aspect of their beliefs to an empirical test? Is any of this that different from superstitious belief in lucky charms?

I really don’t understand such faith.

Not that the bulk of the universe has any reason to care, but Red Hat hosted a little conference in New Orleans last week. Among other speakers, Wil Wheaton was supposed to speak. Given the rest of the agenda, his presentation may well have been the most entertaining of the bunch. However, he cancelled at the last moment.

Now, he is sore about being called unprofessional for doing this. But, barring acts of god, making a professional commitment then not meeting it is the very definition of an unprofessional act. Mr. Wheaton is almost certainly a fine and professional person most of the time, but that does not place one above criticism.

We should not shy away from making ethical or technical judgements upon each other’s actions. LIkewise, we should not shy away from accepting such feedback on our own actions. That is the way toward improvement.

Although less popular than CNN, I watch the weather channel/network all the time. But why?

It may be partly because

- the little pilot in me needs to be aware of nationwide weather, just in case of an emergency call-up to visit Whitehorse, Yukon

- it broadcasts a fundamentally technical matter, leaving no room for deliberate misleading or political bias, beyond the obligatory Hallelujah! when the capital is flooded with backed up sewer juice

- it tries to make an uncontrollable planet-scale phenomenon intelligible, instead of controllable scall-scale human-interest news mystifying

- down-to-earth charmers like Lila Feng (ok, many years ago), Chris St. Clair (a fellow pilot)

For the last six days, I’ve grounded myself with the excuse of thunderstorms.

Flying in thunderstormy weather is a big whole-day-ruiner. While actually encountaring one accidentally is unlikely in GXRP, due to the weather radar and datalink, the turbulence in the area might make one’s teeth shake. So it has been for the last few days: hot muggy air on the ground, unstable air above; thunderstorms popping up randomly over a large area.

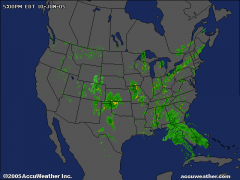

Maybe we are finally approaching a climax of sorts for this weather pattern. At least, I can’t imagine it getting much “better” than this. This afternoon, the entire eastern half of the USA, plus the neighbouring regions of Canada, were boiling with thunderstorms.

I hope it settles down soon. I’m itching to go to the airport, and with certification paperwork completed, rip the “GPS VFR Only” sticker off of the Garmin 430.

UPDATE 06-11: Done!

The same gang running Toronto’s municipal government that has recently instructed parking fines to be increased and enforcement tightened, has just told their staff to start enforcing the anti-idling bylaw.

Out of one side of their mouth, they announce an extreme heat alert. Out of the other side, out comes “… but if you idle to keep cool in your car, you’ll pay!”, never mind the explicit exception of “inclement weather” in the by-law. If one recognizes the greed and galling anti-car bias of these people, the contradiction makes its own kind of sense.

UPDATE 06-14. Some sanity is prevailing on the enforcement side: apparently they issue only “warnings” once the outside temperature reaches 27 C.

There is an old saying that all my G.A.W. performances have corrupted: “that which doesn’t kill Frank, makes Juimiin laugh harder”.

I have had only a few experiences of flying through stormy weather. Yesterday’s day-trip to/from Boston was one.

For the early morning outbound trip, the situation was relatively calm. Air-mass type towering cumulus was starting to form, but it was isolated and easily avoided visually. The weather radar indicated the few hotspots of moisture in my way, and the controllers were responsive to a desire to deviate a few times. My biggest concern on this leg was that, since the major temperature drop from last week, the freezing level was just around my flight altitude (7000 ft). Any higher, or any sudden airborne temperature change, and all the drizzle I was flying through would have become sticky nasty ice.

I dislike ice mainly because it requires me to use the “alternate induction air” doors in the engines. This directs air to visit the exhaust manifold for heating, and to bypass the main air filter. This also causes an unfortunate drop in power output, which in turn slows the airplane down, and reduces climb capability. In moderate icing, this effect, plus the extra drag from the imperfect deicing by inflatable wing boots, limits our Aztec to below 10000 ft on a real good bad day.

Anyway, this part of the trip gave some more familiarization with the operation of the weather radar in mild conditions. I applied several tips from web sites, bu t I’m still just starting to grok it. It was interesting comparing the minutes-old Avidyne downlinked weather data to the live on-board radar images. In some cases, they disagreed with each other, due to the former’s time delay, or due to the latter’s misinterpretation.

For the late afternoon return trip, a low-pressure system located over Maine / Quebec tossed two long NE-SW lines of thunderstorms toward Massachusets and a large mass of moderate precipitation toward Ontario and New York state. I wanted to go home, and the lines were not thick and continuous like a squall, so I decided to launch. I tightly tied down most loose things in the cockpit, especially myself, expecting the occasional roller-coaster ride.

Within five minutes, my cleared route took me straight toward what ATC called a “level 3 and level 4 echo”: a major thunderstorm cell. It showed up as big blotch both on the weather radar (at a parked tilt angle), and on the datalink display, with many friend blotches in a diagonal. Luckily, a gap in the line was sitting right around the GDM VOR. I flew over it on the way in, and is sort of a concentration point for Boston-bound aircraft. I received permission to deviate, then an outright clearance to reroute via that VOR. While this added perhaps fifteen minutes to the trip, it let me pass through the first gauntlet.

The second gauntlet of storms came about twenty minutes later, just entering New York state. (Boy, Massachusetts is a teeny little state. Mother Ontario could fit probably thirty Massachusettses in its land area.) This one too had a conveniently located gap, just slightly south of my path. A deviation was quickly approved. (Perhaps controllers give more such leeway to GPS-equipped aircraft, knowing that they will not get lost even if they get far from the original route.)

The atmospheric conditions during this first hour of the trip are worth trying to describe. Being the single human on board, having decided to hand-fly instead of using the autopilot, I did not have spare time to take pictures. They likely would not have done justice to the view anyhow. It was like this: imagine being in the middle of a giant arena. You can sometimes see walls ahead, a floor below, a roof above, and some gates to pass through. The arena is filled with mist so you can’t see very far. There are wispy structures in horizontal and vertical orientations, extended in one, two, or three dimensions. It all formed a maze sort of like the inside of swiss cheese from the point of view of an ant.

The goal was to fly through as many holes as possible, so that visual contact was possible with the tallest, darkest clouds. If only the airspace was all mine, and I were allowed to swoop down and around and up, it would have been like an amazing real-life version of a video game. In this case, I had to more or less maintain altitude and track, and couldn’t just play. My imagination did what the airplane wasn’t allowed to.

After the two lines of thunderstorms, a single huge mass of moist but tame clouds covered New York state. The Avidyne datalink showed only greens and yellows; the onboard radar showed only a few small red splotches. The afternoon was turning to evening, and these clouds were weakening, so I decided that I would just ride straight through to see just how bad it is. OK, I did swerve here and there, for fun, as practice to stay away from yellow areas, but the deviations were only a mile or two north or south of the course. Even in areas identified by yellow, the turbulence was quite manageable, and the heavier rain simply washed off the dried bug splats from the windshield. (Dirt on the wings remained there after hours of airborne rain wash, probably thanks to a sturdy boundary layer.)

Eventually, I gently descended out of this mass into visual conditions, seeing a wonderful, dusk-sunshine-lit Buffalo / Niagara Falls / St. Catherines area. I even saw Toronto across the lake. The brush of yellow sunshine overpowered the gray clouds overhead and made the ground structures look sumptuous, and not just because the conclusion of the trip was only minutes away. After clearing customs at CYSN, I buzzed visually, barely above Lake Ontario, for the final leg home to the Island. It was an unreasonably short and peaceful cruise. I arrived at home just minutes before official night, which would have required use of a crosswind runway, landing on which would have ended the trip with too much stress. As it was, the final landing was only a mild challenge.

A year after becoming licensed for instrument flight, I’m still new at flying in unpleasantly bad weather. While the airplane is disproportionately well equipped for it, my experience and knowledge could use much more of the sorts of development that this trip produced.

James Randi’s weekly newsletter transcribes a clever little speech from a scientist who’s tired of pseudoscientific garbage.

Oleos are shock absorbing tubes constituting the main flexible connection between the wheels and the aircraft. When an oleo goes bad, the airplane can’t fly.

Well, it can fly, but it can’t land. Consider the construction of an oleo: high-pressure compressible nitrogen, a pool of hydraulic fluid, and a couple layers of nested movable cylinders and rubber O-rings keeping the two apart.

If the O-rings leak, both contained fluids can escape the enclosure. This robs it of its springiness, much like a flat tire. A completely flat oleo has several serious effects. First, of course it can no longer absorb the shocks of taxiing and landing. All those harsh forces would be transferred right to the airframe, possibly damaging the structure.

Second, with retractable gears like those in our Aztec, the oleo is required to extend fully as soon as we are airborne, so that the wheels swing up and into their slots in the nose and the engine nacelles. Flat oleos have no residual pressure with which to fully extend the wheels. This can cause a wheel retraction cycle to smash the wheels into an inappropriate region, possibly crushing gear doors or other structure. The wheels may not come down again. If for some reason flight with a flat oleo is unavoidable, one should leave the gears down throughout the flight.

GXRP’s nose wheel oleo has started seeping the red hydraulic fluid about two weeks ago. It was very slight, and it didn’t stop me from flying with it. The oleo would emit a little bit of fluid just after landing, then seal okay again. But after two or three flights, it was clear that the problem was not getting better, and the pattern of fluid loss could not continue much further. I cancelled several flights over the previous weekend, concerned about a sudden failure, and scheduled an urgent visit at Brantford for a repair. I didn’t realize how close I was.

The Brantford folks kindly allocated an early weekday for the work only two days away. By the time this day rolled around though, the nose oleo has decided to completely deflate. Only about 1/4” of the inner chrome showed. Flying to Brantford for its repair was not safe. Instead, John Cabaco’s maintenance crew right at the Island made themselves available to fix the oleo. It had to be removed and rebuilt, replacing all O-rings and refilling the fluids. 24 hours later, they fit us in and the airplane was good to go. A quick overnight trip to Ottawa Rockcliffe showed the rebuilt oleo working perfectly.

Lessons? Most airplane maintenance shops are willing to handle urgent maintanence like this, even putting some of their scheduled work aside briefly. Owners whose scheduled-work airplanes are sitting for a few more days should not begrudge such temporary reprioritization: they will need it one day.

Also, keep the oleo clean. John suggests using a rag, soaked with hydraulic fluid, to wipe down all oleos before/after each flight. Dirt can be caught by a moist oleo, and its movement can drive the gunk right into the mechanism, shredding the O-ring seals. This can happen surprisingly quickly. The failure modes, as described above, are nasty. So keep them clean!